Introduction

In our last essay, we explored how attitude shapes our sense of what it means to live a good life. We found that attitude isn't a single, solid thing—like a rock we bend down to pick up on a mountain hiking trail. Instead, it turns out to be a mix of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that reflect our state of mind.

We took time to reflect on the many attitudes we carry, especially those tied to how we approach life itself. Each one, we realized, brings its own set of consequences.

Today, we turn to something deeper: belief. What we believe quietly defines what we think a good life looks like—and how we go about pursuing it.

A Good Life and The Declaration of Independence

In the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence, we encounter a powerful idea: that certain rights—life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness—belong to us simply by virtue of being human. These rights aren’t granted by government; they precede it.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

This line expresses a deep belief in personal freedom—the right to choose our careers, relationships, and spiritual paths without interference. But the authors didn’t stop there. They understood that freedom without protection can be fragile, even dangerous. So, they insisted that governments exist only to protect these rights, and that power must come from the people themselves:

“That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed…”

The framers recognized that if government fails in this role, it’s not just our right—it’s our responsibility—to change it. That’s belief, not just policy: a vision of what a good life requires, and how it must be defended.

Belief In Inalienable Rights and the U.S. Constitution

When the framers ratified the U.S. Constitution in 1787, they did so with a clear-eyed belief: human beings are prone to self-interest, and power tends to corrupt. They envisioned a government strong enough to maintain peace and order, yet limited enough to prevent tyranny. To strike this balance, they created a system of checks and balances, anchored by a separation of powers. The goal was to keep any one person—or group—from dominating the whole.

Shaped by their conflict with England and steeped in the values of the European Enlightenment, the framers understood the dual nature of humanity. They sought to elevate the better angels of our nature while placing guardrails around its darker impulses—greed, ambition, and misdirected self-interest. As James Madison put it in Federalist No. 51:

"If men were angels, no government would be necessary."

Do We Need a “Governor Switch” To Live a Good Life?

When I was a senior in high school, our band took a long, achy school bus ride from Plattsburgh to Buffalo. Eight hours of bouncing in seats that felt more like medieval torture benches than transportation. Somewhere around hour four, I wandered to the front of the bus and asked the driver,

“Can you drive any faster?”

He squinted through bird splatter on the windshield and said, “I’d like to. But the school installed a governor switch—I’m capped at sixty.”

I blinked. “What’s a governor switch?”

“It’s a device that stops the bus from going over a certain speed. Once I hit sixty, it cuts off extra fuel so I can’t go faster—even if I wanted to. Keeps us from ending up in a ditch full of teenagers, I guess.”

Back in my seat, I thought about that. It felt unfair to restrict a driver who wanted to go faster—but it also made sense. Not every driver can be trusted to handle more speed responsibly.

I think some of our beliefs work the same way. They act like a governor switch—quietly limiting how fast or far we go, not to restrict our freedom, but to keep us, and others, safe on the ride.

Two Competing Beliefs on How to Live a Good Life

Two influential thinkers offer competing views on what it means to live a good life within society.

The first comes from the 19th-century English philosopher and political economist John Stuart Mill. In On Liberty, he writes:

…The only freedom which deserves the name, is that of pursuing our own good in our own way, so long as we do not attempt to deprive others of theirs, or impede their effort to obtain it…

Mill championed the individual. He believed people should be free to move, grow, and build their lives as they see fit—so long as they don't harm others. No government, he argued, has the right to restrict that freedom without cause.

Emile Durkheim, the 19th-century French sociologist, saw things differently. Society, he believed, isn't just a loose contract between free individuals. It’s a living system that depends on cohesion, shared values, and social responsibility.

Left entirely to our own devices, Durkheim warned, we tend to chase shallow pleasures or self-interest—often to the detriment of the greater good. A truly functioning society must apply pressure: not to oppress, but to guide.

From this perspective, limits on autonomy aren’t threats to freedom—they’re tools for shaping character and reinforcing the social fabric.

Murder And the Obsessed Teenage Video Gamer

Sometimes, extreme examples help clarify the stakes. More than twenty years ago, in England, a 14-year-old boy was brutally murdered by a 17-year-old who, according to friends and family, was obsessed with a violent video game called Manhunt. The game encourages players to carry out gruesome killings. The murder bore eerie similarities to actions in the game.

What would Mill say about this? Of course, he would never condone murder. He argued for personal freedom—so long as it causes no harm to others. But this tragedy shows the limits of that principle in practice.

How did this teenager become so detached from society that he could see life as a private, isolated existence—disconnected from others? And what about the game itself, marketed to adults but accessed by minors?

When people are left entirely to pursue their own version of a “good life” without guidance or accountability, the consequences can be catastrophic. A belief system that honors only personal desire, without anchoring it to something larger—community, meaning, responsibility—can slowly unravel a life.

No grounded, healthy teenager with a sense of belonging and purpose behaves this way. Something deeper failed here. And belief, or the absence of it, played a role.

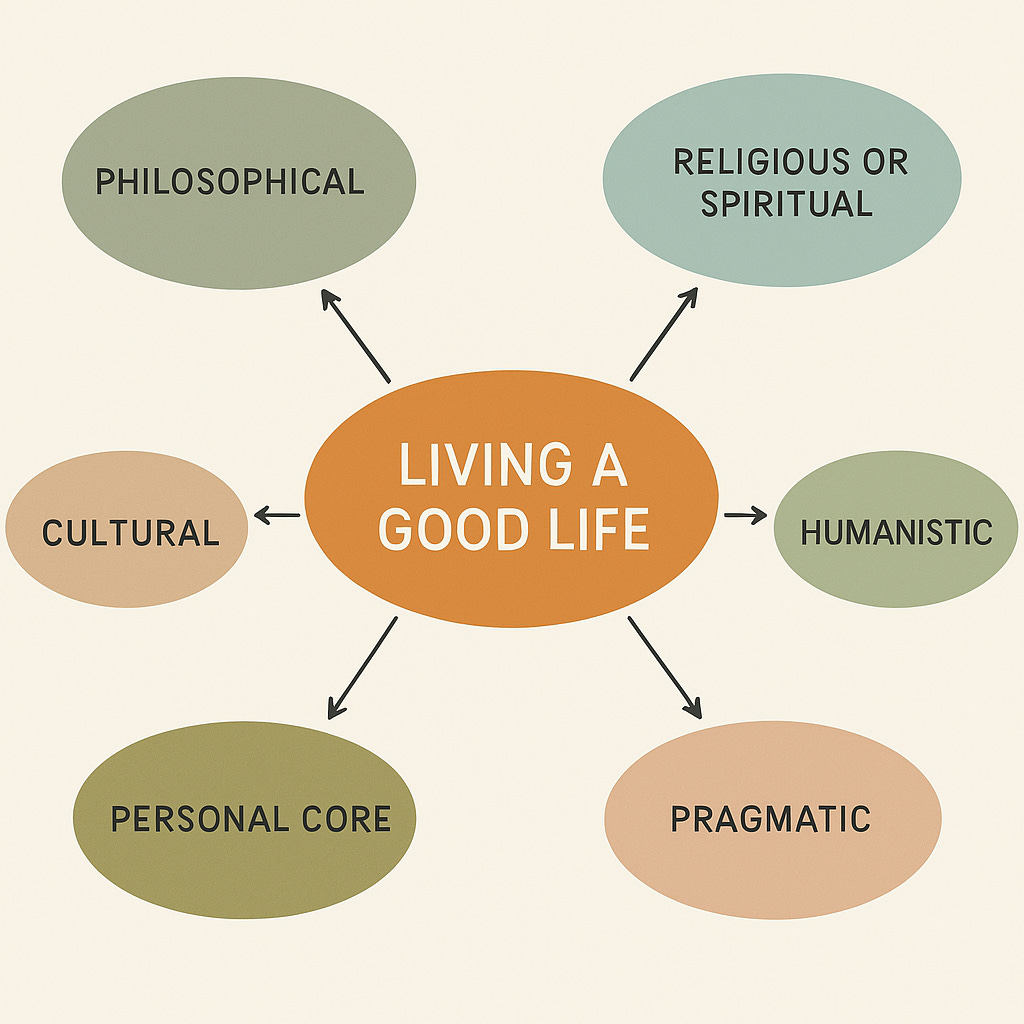

Where Do Our Beliefs Come From?

Our beliefs don’t come out of nowhere. We shape them through personal experience and the culture we swim in—often without realizing it.

I’ve known people who see no issue with sleeping with married partners—whether they’re single themselves or married, too. Others treat sex like a scoreboard, chasing numbers instead of connection.

Whether we realize it or not, these choices reveal what we believe about relationships, responsibility, and the worth of another human being.

Beliefs run deeper than attitudes. They shape how we see ourselves, how we interpret the world, and how we relate to others. Like the Cowardly Lion in The Wizard of Oz, who believed he lacked courage—and acted accordingly—we live out the consequences of what we believe, whether true or not.

Conclusion

It’s worth taking time now and then to examine our beliefs. Some may be outdated. Others might have quietly shifted without our noticing. And some still serve us—but deserve a second look.

That’s why I created a Belief Inventory Practice Exercise—to help you reflect on what you truly believe, and how those beliefs shape your life.

You can work through it at your own pace. You might be surprised at what rises to the surface.

Until next time—here’s to your Spiritual Health!

Belief Inventory Practice: What Do I Really Believe?

Step 1: Identify the Life Domains -Write down these core areas of life:

Self-worth & identity

Relationships & love

Work & purpose

Money & security

Health & the body

God/Spirit/Life

Suffering & injustice

Death & what comes after

Step 2: Free-write what you believe (no filter). For each domain, complete the sentence: "I believe that..." Write 2-3 beliefs for each area, even if they contradict each other. Be honest - write what you feel you believe, not what you should believe.

Step 3: Ask: Where did this belief come from? Next to each belief, write: "I got this from..." (parents, culture, religion, trauma, teacher, experience, intuition, etc.)

Step 4: Ask: Is this belief helpful? Next to each belief, write: - "This belief makes me feel _______."- "This belief leads me to act _______."- "Is this belief true? Always? For everyone?" Then mark: (OK) = Belief is aligned and empowering. Mark (!) = Belief may be limiting, outdated, or unexamined

Step 5: Replace or reframe: For (!) beliefs, ask: "What could I believe instead - something truer, kinder, and more empowering?" Write new affirming or empowering beliefs where it feels right.

Step 6: Choose 1 belief to live from this week Pick one new or clarified belief and commit to living as if it were completely true for 7 days. Write it down. Post it somewhere. Watch how it changes your choices.

Belief inventory--what a good idea!